Einn af þeim mörgu hermönnum sem voru hér á stríðsárunum var Anthony Adams. Hann þjónaði í breska flughernum og var þar í Royal Corps of Signals. Mér áskotnaðist nokkrir af þeim pappírum sem hann hafði með sér heim frá Íslandi. Hann tók saman skemmtilega grein á ensku sem ég ætla að þýða einhvern daginn en hér er hún.

Recollections of Iceland in 1941 and 1942

In late September 1941 after 4 days at sea escorted by two destroyers we disembarked from the ex Norwegian Liner Bergensfjord at Reykjavik, capital of Iceland a town of about 39,000 inhabitants, we found the temperature surprisingly mild. We airmen, earmarked for Royal Air Force Station Reykjavik were of different trades, a school friend name of Max Baer by co-incidence was on board, his trade was cook and butcher, his home was about six doors nearer in Ipswich than mine on the Woodbridge Road, at Rushmere St Andrew.

No time was lost transporting us to the aerodrome comprising mostly Nissen Huts, small for barrack huts and larger but similar for mess halls and N.A.A.F.I. buildings. For warmth the barrack huts were lined with half inch thick insulation wood pulp panels which we called Tentest, a coke burning tortoise stove was in the centre of each hut and we would use waste pieces of the boarding panels, easily broken, soaked in paraffin for a quick fire. Our bedding was a comfortable quilted double sleeping bag lying on a brown wool blanket on a wire bed supported by four petrol cans.

A number of us made up the signals section personnel, wireless operators, telephone operators with an exchange and teleprinter operators. We operated a four watch system. 1600hrs to 2400hrs 1200hrs to 1600 hrs 0800hrs to 1200hrs and 2400hrs to 0800 hrs then 48 hours off. In charge was a genial flying officer Salt. We had a portable wind up gramophone in the section so late one night we sent a music programme over the telephone to colleagues at AC/HQ Reykjavik. It seems like only yesterday when we played “Twenty miles to nowhere” and Harry Roy’s “When a lady meets a gentleman down south” Not long after, about midnight, the telephone rang, the caller claiming to be the Chief Signals Officer! As if! At that unearthly hour! but it was! and the whole watch had to see F/O Salt next morning. I believe he was slightly amused; anyway he let us off with a caution. In another scrape with authority, we ran out of coke, we were cold so I volunteered to ‘borrow’ some from a nearby army compound, apprehended in the middle of the deed and put on a ‘fizzer’, a charge that is. Hauled up before the duty officer who asked my age “Twenty sir” I replied “and you start stealing at your age” I unwisely said “I don’t call it stealing sir” reasoning that we all worked for the same firm “Well I b***** well do! Five days CB!”

Much of our off duty time was spent in the hut where we would write letters home, play cards, a favourite being solo whist, although it might also vary from pontoon to bridge.

We had a radio driven by a car battery and during the winter months we could receive medium wave stations from both U.K. and America but in summer only Radio Reykjavik and shortwave stations could be received. We had a free cigarette ration of 200 a month along with some chocolate; being a non-smoker I exchanged my cigarettes for chocolate.

The food in camp was not wonderful with porridge occasionally tainted with paraffin, Icelandic mutton alternating with Maconochies tinned meat and vegetable ration, by no means our favourite dish, occasionally Icelandic rhubarb and when bread ran out, as it often did, we were fed hard biscuits.

Entertainment was provided on occasions by the resident Cyril Stapleton orchestra with singers Denny Dennis and Sam Costa. On a church parade the Royal Air Force march sounded comical played by a dance band. There was the camp cinema which I visited several times but later the Tripoli cinema on the other side of the airfield for American forces showed more recent films and it was there I saw Glen Miller’s ”Sun Valley Serenade”with Tex Beneke, Lynn Bari, John Payne and Sonja Henie an excellent film.

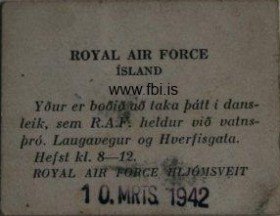

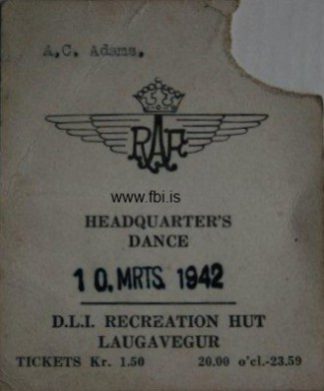

On March 10th an RAF dance was held at the D.L.I. army recreation hut Laugavegur og Hvervisgata. I always assumed D.L.I. meant Durham Light Infantry whose members incidentally wore a polar bear shoulder flash but RAF personnel were not allowed to wear the polar bear badge. I paid just one visit to the swimming pool in Reykjavik the water being heated from the hot springs up country and transported by pipeline. The hot springs also heated greenhouses hence the abundance of tomatoes in the shops. The main shopping street was on a slope and besides local produce shops sold mostly American goods, stationery, silk stockings. I bought a Sheaffer fountain pen and two spiral exercise books, 10 lemons, 2 pairs of Kayser Bondor at 11.50 krona a pair, at the time 1 krona was equal to 9d or 26 to a pound.

The weather was changeable, in summer very pleasant just like late spring in England in June to August we would often lay in the sun on the nearby hillside. We soon got used to the long summer days in this latitude and the darkness of winter. When there was no wind, which wasn’t often, winters were cold and dry and quite bearable, I remember one night running from the hut in only P.T. shorts the temperature being 2 degrees Fahrenheit. The lake in town froze over and was a magnet for skaters. On the night of Thursday 15th January 1942 a gale starts, all personnel not on duty were recruited to hold down aircraft with ropes. Exposed huts were blown into the sea, the wind speed reached 135 mph. Planes were blown into each other and 5 American planes sunk in the bay. Surprisingly, no damage was reported to planes or Nissen huts from nearby Kaldadarnes. On this date the U. S. Cutter Hamilton in the vicinity reported 20 men reporting to sick bay with bruises and contusions while responding to an SOS from the freighter S.S. West Kebar. By the morning of the 16th the hurricane was completely gone leaving 17 fellows killed. Our barrack huts escaped the worst being sheltered by the nearby hill.

We were able to see some of Iceland’s attractions during leave and off duty periods. A party of us from the signals section visited the impressive Gullfoss falls and rapids, then the Great Geyser into which we threw bars of soap to encourage it to perform but no luck. There were numerous small hot springs, one a striking blue and very hot. Thingvellir Iceland’s National Park was impressive with rock formations, mosses and lichens. We finished the visit with an extravagant meal at a ski club which cost us 13 krona each, roughly ten shillings. There was another occasion when The Station Commander, a group captain, invited six of our shift who were off duty to accompany him mountaineering. We climbed the mountain and on reaching the summit found a brass plate screwed onto the rock giving names and dates of climbers of some 60 years earlier. Another attraction the Aurora Borealis or Northern Lights would sometimes display spectacular vertical moving light curtains in the night sky.

Icelandic roads in the 1940’s were rough and narrow with only one metalled road extending 3 miles out of Reykjavik. The buses built on American Reo Speed Wagon chassis were narrow, to cope with narrow roads and bridges. Some buses were dual purpose vehicles passengers in the front and freight in the rear. The roads were surfaced with crushed red volcanic rock and very dusty in summer. The air was polluted with volcanic dust, noticeable by the brown layer settling on our best blue hanging in the huts, called best blue as it was for parades, special occasions and walking out. There were, in the war years, no trees in our area but I understood there were some fir trees in the far north at Akureyri, Iceland’s second town of around 5,500 inhabitants. I met an Icelander name of Bjarni Marcussohn who called at the hut, attracted by a strong smell of ripe apples, seldom seen in wartime Iceland. We exchanged photographs, I still have his somewhere.

We were granted some most welcome leave on March 18th 1942 this because Reykjavik was classed a ‘Home Station’. We weighed anchor at 2200 hours; the boat was a dreadful tub, rumoured to be an ex. German supply ship from the “Altmark” incident and added an extra day at sea. Leave was extended to 28th April, when leave was over; we boarded at Greenock the very excellent clean, fast RMT Leinster which was even equipped with a hospital ward. We docked at 1100 hours with the best part of our stay to come with visits to places few of us would ever have seen. Before ending I should mention Toch H a welfare organisation founded in World War One by the Rev.Talbot had a presence in Iceland and produced a magazine appropriately named “Northern Lights” for the forces stationed in Iceland.

Our tour of Icelandic duty finally finished in December 1942 and again we had the speed and comfort of the Leinster and on board who should I meet again but Max who I met on the Bergensfjord on the outward journey and hadn’t seen since and with that comes the end of my Iceland saga.

Anthony Adams 18th July 2009.

LAC Anthony Adams Iceland hut A9 RAF Reykjavik 1941

Ekki amalegt að geta boðið dömunum svona miða.

Dansleikur.

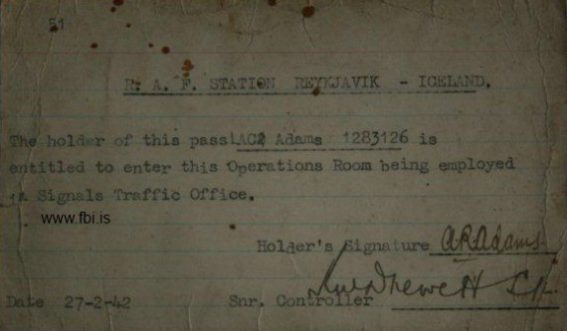

Leyfisbréf fyrir aðgang.

Stimpill RAF á Íslandi.

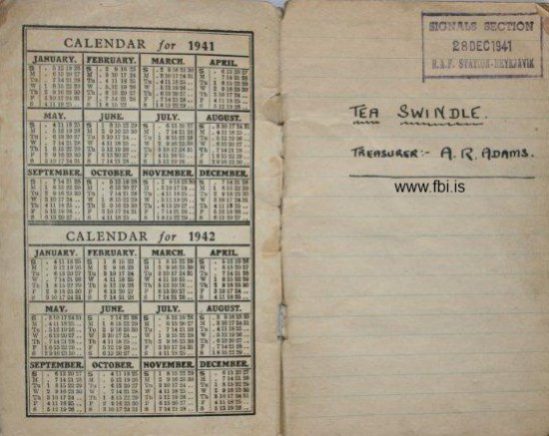

Sjóðsbók.

TOC á Íslandi 1942.

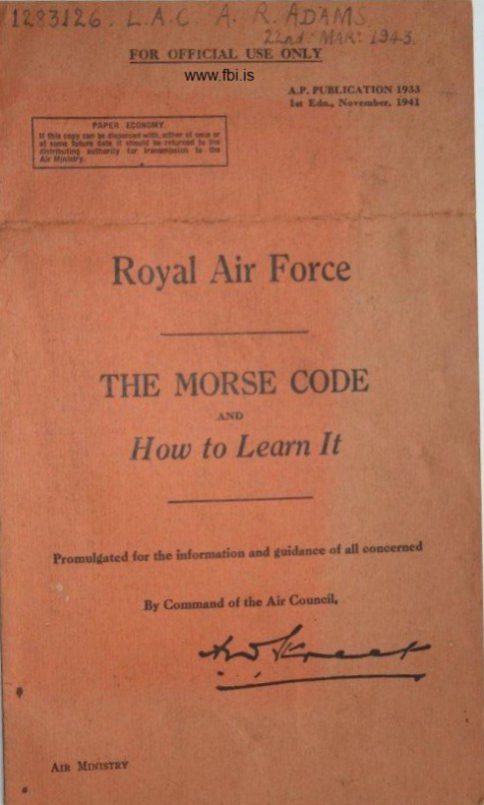

Blöðungur um morskerfið.